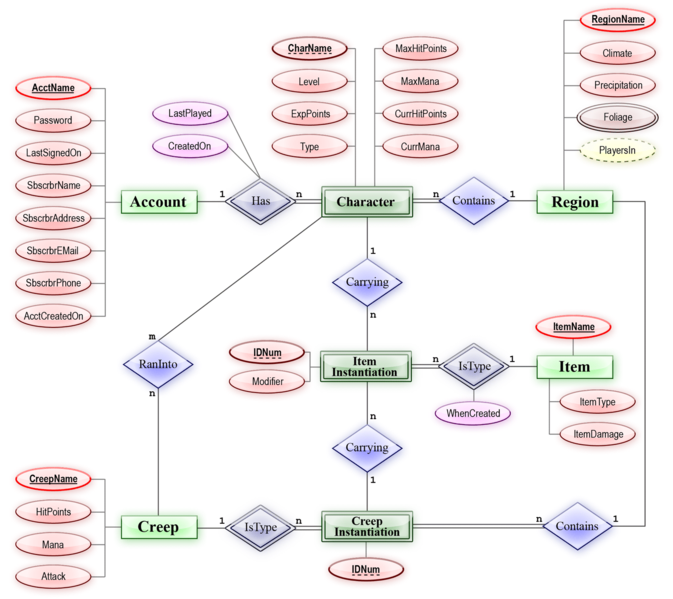

I was recently training a new software developer, explaining the joys of three-tier architecture and the importance of the proper black-box encapsulation, when the subject switched to database design and ER diagrams. For those unfamiliar with the subject, entity-relationship diagrams, or ER diagrams for short, are a visual technique for modelling entities, aka tables in relational databases, and the relationships between the entities, such as foreign key constraints, 1-to-many relationships, etc. Below is a sample of such a diagram.

I. The Theory

Like many enterprise technologies, ER diagrams can be a bit of an overkill in single-developer projects, but come in handy as soon as you need to explain your design decisions to a room full of people. Since a software application is only as flexible as its underlying database, ER diagrams help define the initial set of business rules for how people will be able to interact with the system. As a software development practice, they are often encouraged, but in medium to large companies, they may be absolutely required. There are enough tools now to create ER diagrams quickly and easily, many of which will generate SQL database creation statements for a variety of platforms directly.

II. The Practice

Due to tight time constraints and ever-expanding scope creep, I find most developers skip creating or maintaining ER diagrams whenever the opportunity arises. One telling example of this is a developer who creates a diagram, starts building the application, and realizes their initial diagram was completely flawed. Given that they are now behind schedule because they made mistakes in modelling the data, they do not have time to go back an update the model, and their ER diagram becomes a distant memory compared to the final database. Most managers would rather see finished software products than accurate diagrams, although will take both if offered.

ER diagrams are incredibly useful in the early stages of designing a new application, but as an experienced software developer, I spend more time enhancing and maintaining databases than I do creating them from scratch. Furthermore, it can be difficult to create an ER diagram for an existing database, especially if you were not involved in its creation. Even when companies do maintain ER diagrams, they tend to be months, often years, out of date, as it can be difficult to motivate each and every software developer to update the database documentation after making a change.

III. Where’s your database’s ER Diagram?

What about your software application? Is there now or was there ever an ER diagram for your company’s database? Is it 100% accurate to the current production database? I’d like to hear from other developers to find out if people are diligently maintaining ER diagrams, or if it is really a common practice to let them fall by the wayside after a database is established.